(Work in progress…)

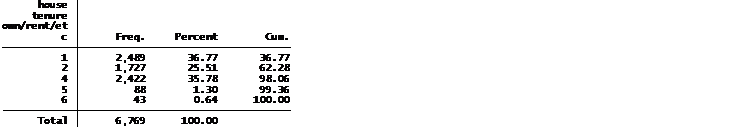

An example of a time clock rounding analysis in a wage and hour case. In this case, we describe a case example involving a large mid western employer. The data utilized in this analysis is the time data received for the February 28, 2003 to December 18, 2011 time period. The data contained 66,452 records.

In this wage and hour time rounding case the defendant and plaintiff disagree on a number of key data issues. One party states, that in his analysis “all 66,452 shifts described in the data set were considered.” The other party states that this statement is completely incorrect use of the data in this case. First and foremost, they argue that there are 13,877 records which do not have any rounded time entries or punch time entries. It appears as though one party utilized these records in his calculations of percentage

In those records where there are no time entries, the record would appear to have neutral rounding (that is, blank compared to blank). Including these records in the data artificially increases the number of neutral rounding. One party argues that this is especially problematic because the opposing expert includes the neutral rounding in with the rounding in one party’s favor, which distorts the results.

Second, parties argue that there are an additional 7,089 records with inappropriate pay code names that should not be included in the meal or rounding analyses. These codes have duplicate entries of the time data, no hours paid, or have $0 associated with them in the pay data.

Third, further analysis showed that there are an additional 8,245 records that have duplicate entries for the start time, end time, and punch times from other records on the same days. These records also contain paid hours that would need to be included in determining the total number of hours paid in a particular day. For these records, the number of hours paid should be included in the total number of hours paid for that day. However, the parties argue the rounded time and actual time worked should not include the duplicated time records for these days.

After the three cuts described above, one side argues that the remaining 35,000 or so records are the appropriate starting point for the analysis. The parties argue that utilizing the data cuts results in drastically different results in the time clock rounding analysis.

- Definitions:

- Total rounded time is calculated from the start and end times in the data. Total actual time is calculated from the punch in and out times in the data. The amount of time that was rounded is calculated by comparing the rounded time to the actual time worked.

- The percent of punch sets with time gained is the number of instances where the punch set showed a rounding in the employees’ favor, divided by the total number of punch sets. Whereas the percent of punch sets with time lost is the number of instances where the punch set showed a rounding in the employers’ favor, divided by the total number of punch sets.

- Time gained due to rounding is the total amount of time rounded in instances where the punch set showed a rounding in the employees’ favor. Time lost due to rounding is the total amount of time rounded in instances where the punch set showed a rounding in the employers’ favor. Net time gained / lost due to rounding is the sum of time gained and time lost.

At its core, the analysis of time clock rounding allegations in a wage and hour or FLSA case is straight forward That is, the analysis typically involves determining if the time clocking rounding was neutral or did it favor the employee or employer, more times than not?

At its core, the analysis of time clock rounding allegations in a wage and hour or FLSA case is straight forward That is, the analysis typically involves determining if the time clocking rounding was neutral or did it favor the employee or employer, more times than not? Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA)

Injury Compensation Reform Act (MICRA)